47 Savin Avenue, Norwood

In 1909, INTO (Finnish for “zeal”), a local chapter of the Finnish Workingmen’s Association, opened a retail cooperative store in the Swedeville area of Norwood. The small building had previously served as a chapel for area Swedish Lutherans and Baptists. In 1917, INTO, a socialist organization, tore down the building and replaced it with a larger one.

Its name notwithstanding, Swedeville was the center of Norwood’s Finnish community. The neighborhood emerged as an enclave of Swedish immigrants within Norwood in the 1890s. Finnish immigrants began populating the area in the first decade of the 1900s and soon outnumbered Swedes. By 1914, there were 500 Finnish immigrants in Norwood.

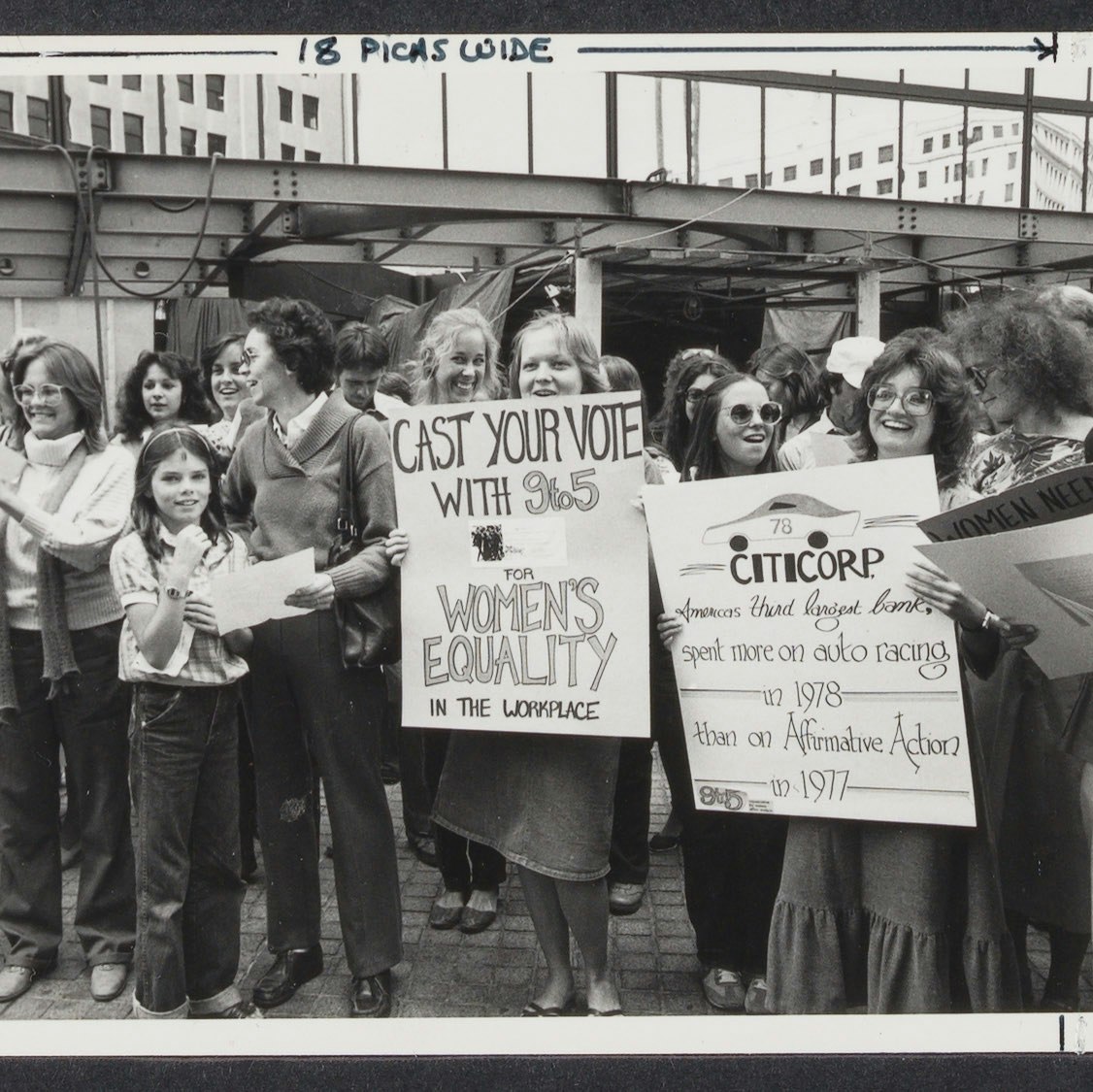

As manifested by the existence of the cooperative, Finnish immigrants to the United States often embraced socialism—in no small part due to their experiences of injustice in their home country, “They joined the Socialist Party of America in greater numbers than any other ethnic group,” writes historian Patricia Fanning, “and were consistently at the forefront of demands for workers’ rights and unionization.” Reflecting these politics, Norwood Finns established INTO in 1904, and the group soon joined the Socialist Party and the Finnish Socialist Federation. Two years later, INTO built Finnish Hall, with volunteer labor, on Chapel Street (37 Chapel Court).

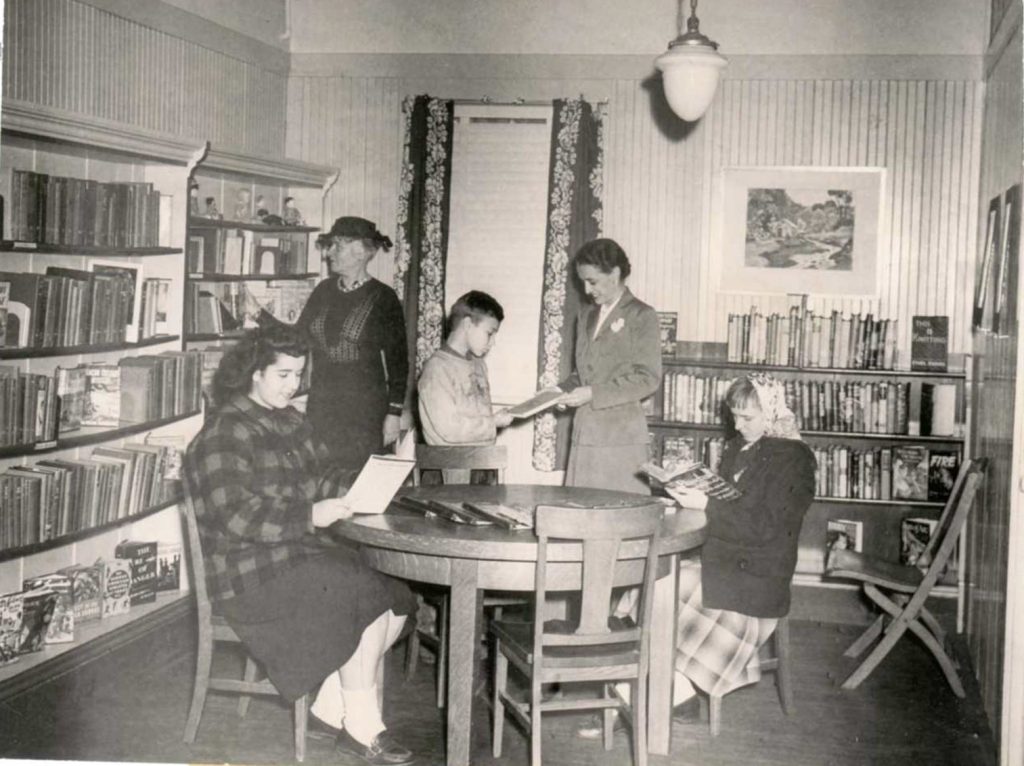

The cooperative was one of many of INTO’s activities in Norwood; they ranged from drama groups and athletic clubs to a choir and a women’s sewing group. Finnish Hall also housed a library and hosted educational and political lectures as well.

As a socialist enterprise, the INTO store returned excess revenues to its customer shareholders. According to one account, the enterprise grossed $200,000 in 1920 (the equivalent of about $3.2 million in 2025). It “provided meat, groceries, dry goods, shoes, and a restaurant.” It also ran a milk bottling and distribution plant in the neighboring town of Walpole.

Initially, the store was a branch of “Turva,” a cooperative store in Quincy that had opened four years earlier. A decade after its founding, the Norwood undertaking (as well as its sister store in Quincy) joined with other Finnish cooperative associations—in Gardner, Fitchburg, Maynard, and Worcester, Massachusetts; and Milford, New Hampshire—and became part of the United Cooperative Society, with its main office in Boston.

The United Cooperative Society effort did not last long. The years 1919-1920 were a time of highly unstable prices as well as political splits among socialists. These factors contributed to modest profits the first year and economic losses the second for the network of cooperatives. As a result, the society decided to give up its office in Boston and for each member store to resume its autonomy, while maintaining the “United Cooperative Society” name but with the location name added on (e.g., United Cooperative Society of Norwood).

The Swedeville store did well in the subsequent decades. However, as supermarket chains expanded into Norwood, the cooperative establishment was at a disadvantage as it could not compete with their prices. In 1953, the store ended its operations.

The building which once housed the United Cooperative Society of Norwood store is now a private home.

Getting there:

An MBTA bus that runs between Forest Hills Station (Orange Line) and Walpole passes within a few blocks of the site.

To learn more:

Patricia J. Fanning, Keeping the Past: Norwood at 150, Staunton, Virginia: American History Press, 2021.

Savele Syrjala, The Story of a Cooperative: A Brief History of United Cooperative Society of Fitchburg, Fitchburg: United Cooperative Society, 1947.

H. Haines Turner, Case Studies of Consumers’ Cooperatives: Successful Cooperatives Started by Finnish Groups in the United States Studied in Relation to Their Social and Economic Environment, New York: Columbia University Press, 1941.